The intellectual property (IP) provisions of the Trans-Pacific Partnership continue to generate significant debate. Rather than discussing the agreement itself (my previous thoughts can be found here), in this post I will focus more broadly on Canada’s position in the global trade of ideas. As the figures below illustrate, our position is not enviable. In particular, our stagnant IP exports and growing IP trade deficit raise concerns about our ability to successfully commercialize our ideas abroad. Coupled with other indicators pointing to a decline in business R&D, particularly among Canada’s top firms, it highlights the need for government and the private sector to more effectively support Canadian innovation and IP exports.

Canada has a Persistent (and growing) Trade Deficit in Ideas

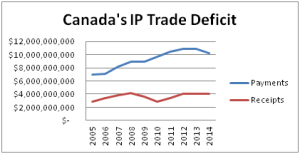

The chart below shows the gap between Canada’s IP payments (imports) and receipts (exports) over roughly the last decade. As the chart shows, Canada has long been a net-importer of IP, with the gap between payments and receipts expanding since 2005. But while Canada’s IP imports have grown consistently – increasing from just under seven billion in 2005 to over ten billion in 2014 – our IP exports remain stagnant. Indeed, Canada’s IP exports in 2014 were below those recorded in 2008. As a result, our annual IP deficit grew from $4,084,504,075 in 2005 to $6,179,623,294 in 2014. This suggests that Canadian firms are continuing to import technological innovations, but may be doing a poor job of commercializing their own technologies abroad.

Explaining IP Deficits & Surpluses is Not Straightforward

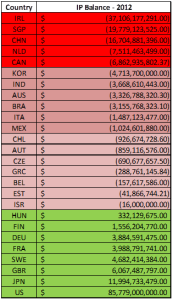

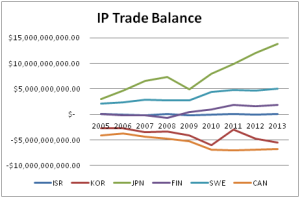

It’s tempting to link Canada’s IP royalty deficit to our country’s poor performance in research and development spending. And indeed, a quick comparison of countries’ IP royalty balances and R&D spending suggests there is at least some association between the two. As a general trend, countries that perform well in business R&D and gross expenditure on research and development (GERD) also tend to perform better in their IP royalties balances. Moreover, large developed countries with very large economies such as the US, Japan, the UK and Germany all boast surpluses while smaller countries or emerging markets are more likely to run IP deficits. But the relationship is not straightforward and, in the case of the latter, there are significant exceptions. Most notably, a number of small countries including Sweden, Finland and Hungary, maintain IP payments surpluses.

What about the top per-capital spenders in business research and development? Among these countries Japan, Sweden and Finland enjoy a healthy net influx of IP payments, while Israel has a relatively even balance of payment inflows and outflows year over year. Conversely, despite its strength in research and development, South Korea maintains a significant trade deficit. Korean policymakers continue to view this situation as a cause for concern. For their part, some analysts have tied the countries IP deficit to the country’s large tech firms, like Samsung, and their heavy reliance on foreign technologies, while others have highlighted the need for a greater focus on the role of startups and small companies. Ireland and Singapore are similarly notable for both their relatively healthy level of BERD and their large IP deficits.

Canada’s IP Deficit is Unsurprising, but it’s Growth Could be Cause for Concern

It is tempting to treat IP trade balances as analogous to those in trade in goods and, in so doing, suggest that concern over persistent and growing royalty deficits is misplaced. Exchange, after all, should be mutually beneficial, or else it would not take place. And while foreign firms are benefiting from the payment of royalties, domestic companies can benefit from the ability to acquire ideas and technologies that would otherwise not be available to them and subsequently spawning further innovation and product or process improvements.

Unfortunately, it’s not that straightforward. With the expansion of patents and patentability, companies increasingly pay – or are made to pay – simply for freedom to operate in a particular technology area. In this context, payments made to foreign companies may be less about securing necessary and innovative technologies and more about paying rents to rights holders wielding blocking patents or to navigate increasingly complex patent thickets. In addition, licensing costs also have the effect of excluding potential domestic technology users, thereby blocking further innovations. Finally, acquiring technology from abroad, rather than generating it domestically, may leave a country less able to generate follow-on technology innovations. And in a global knowledge economy, being merely a technology consumer – rather than an active contributor to ongoing processes of innovation – is arguably a dangerous position.

Moreover, as with more traditional trade-in-goods, countries around the world are seeking to use regulatory and other policy mechanisms to advantage their domestic firms and industries. These policies include – but are not limited to – strengthened intellectual property provisions in international agreements that will result in gains for intellectual property exporters. Other prominent policy mechanisms include the so-called patent box IP treatment, the creation of various types of sovereign patent funds (SPFs), subsidies for patenting activity by domestic nationals, and the use of intellectual property rights as a way to damage competitors or disrupt trade in finished goods. And while much of this is self-defeating, countries that fail to adopt similar strategies may lose more over.

The existence of an IP deficit alone is not necessarily a cause for concern. Indeed, as a small country located next-door to the world’s largest innovation economy, Canada could be expected to run an IP deficit. More concerning is the growth of the deficit and stagnation in our IP exports in recent years. Read in conjunction with other indicators – such as declining business spending on research and development – our growing external payments deficit in IP raises important questions about our ability to successfully commercialize our ideas abroad and the broader status of Canadian innovation. As the government considers how to best boost Canada’s lagging economy, it would be advisable to focus on improving our position in the global trade of knowledge and ideas.